The Dictatorship of the Articulate

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.”

— Shakespeare

A few years ago, Silicon Valley was buzzing with the reverberations of Marc Andreessen’s epic essay, It’s Time To Build.

In case you haven’t read it, It’s a formidable pep talk, a call to arms for builders, and an exhortation to take stock of the forces standing in the way of builders.

These obstacles are, mostly, institutional — too many people have seats at too many tables, each with the power to block, none with the authority to approve.

We are currently discovering the disastrous consequences of this system — Peter Thiel has talked about it for decades, and Tyler Cowen called it “The Great Stagnation.”

Something’s off

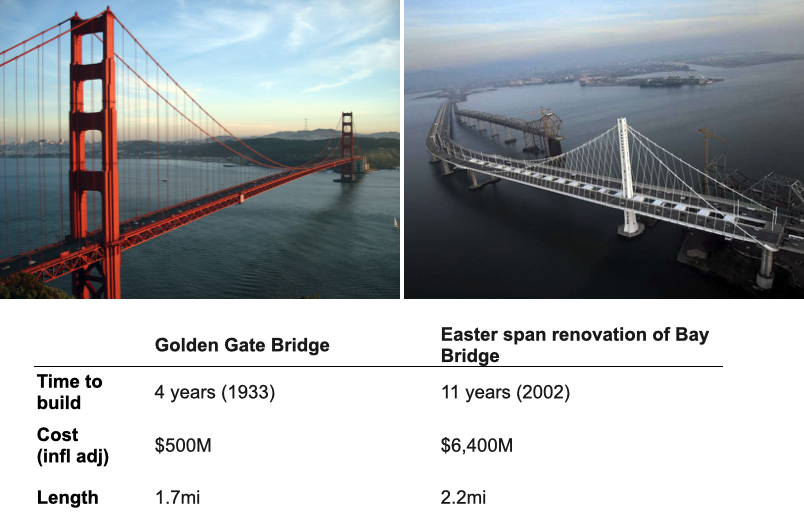

It does seem like something is wrong when the past feels like some wondrous foreign land. We built the Golden Gate Bridge in only four years. Then, to celebrate, we built an artificial island in just two. That’s less time than it now takes us to decide that a laundromat isn’t a historic building and that, fine, you can build some apartments over it.

70 years after building the Golden Gate Bridge, we completed the Eastern Span Renovation of the Bay Bridge. It took 3 times as long and cost 13 times as much(!), adjusted for inflation. How did bridges become 13 times as expensive in 70 years?

A few years ago, I asked my grandmother how the world had changed in her lifetime. She told me:

“- I remember how happy I was when we got running water! I must have been 15.

– Wait, 15? How did you go to the restroom before then?

– Well, it was less of a restroom and more like a wooden shack in the garden, with a hole in the ground.”

She then told me of when she got her first fridge, her first TV, her first dishwasher, her first microwave. I asked her, perhaps with the smug complacency characteristic of our generation, what she thought of the tech revolution. Isn’t it cool that we can see each other on FaceTime despite standing 8,000 miles apart?

“It’s fine,” she said. “But it’s no running water.”

A lot can happen in 30 years

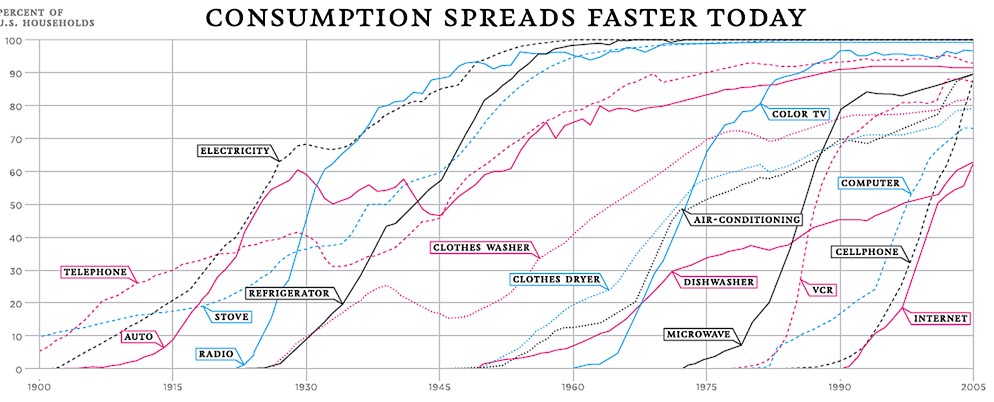

Inventions that took place from 1900 to 1930 include the plane, the automobile, the washing machine, the radio, the television, frozen food, penicillin, plastic(!)

That’s in 30 years. Hell, no household in the country had access to electricity in 1900. In 1930, more than two thirds did.

30 years ago was 1990. What’s happened since then? The Internet and smartphones, mostly. And still we complain things are changing too fast. And don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying these things are unimportant. They’re huge. But they’re no running water.

How did we get there?

It’s tempting to explain the slowing pace of innovation by our having already picked all the low-hanging fruits. Former head of the US patent office Charles Duell agreed: “Everything that can be invented has been invented,” he yelled from a hole in the mud in 1899.

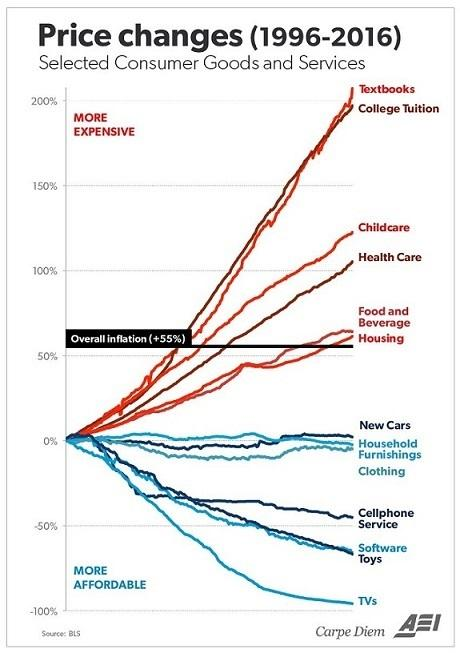

It’s a funny coincidence that the field where we’re seeing the most innovation happens to be the one we regulated least, and that the fields that got worse are the most regulated ones.

What’s the most important change that happened in the world of atoms in the last 30 years? Uber may be near the top the list — it has changed how we move in cities.

Now, Uber is an app that lets people drive people in their cars. Think of how controversial that was, and ask yourself why we’re not seeing anything above that water line, when even this barely made it.

Finally, I find it rich to call things like the Model T, Apollo 11, or nuclear energy “low-hanging fruits.” What must we then call the kick scooters we could barely put on our sidewalks?

As Marc Andreessen remarks, in every case, the culprit is regulation.

Building has become illegal in the US, whether it’s housing, drugs, universities, or mask factories. The economy is like a car driven by two people — one with their foot on the gas, the other on the brakes. Silicon Valley has a bias for pushing harder on the gas. But it’s becoming clear that we won’t go much further if we don’t get our foot off the brakes.

Too many seats at the table

In Why Nations Fail, Daren Acemoglu draws a distinction between inclusive and extractive institutions, proposing that over the long run, inclusive institutions — those giving a voice to the most constituents — will lead to the most growth.

Inclusivity is fine, but our current situation makes me wonder if we got too much of a good thing. There is always a loser to any change — even when it’s an otherwise overwhelming net positive. As Joel Mokyr points out in The Lever of Riches:

Invention is something of a hostile act, a dislocation of existing

schemes, a way of disturbing comfortable bourgeois routines.

Technological progress requires above all tolerance toward the

unfamiliar and the eccentric.

This problem of “too many seats at the table” is pervasive: you actually have to ask for your competitors’ permissions before you can open anything, from a hospital to an ice cream shop. We’ve never had so few rights over our own property, and so many over that of others.

There can be no innovation if the status quo gets a say: creation cannot need a permit to destroy.

The dictatorship of the articulate

But I don’t think our institutional woes stem only from politics — there’s a deeper cultural issue at play, and everybody should wonder to what extent they contribute to the problem.

Everywhere I look, I see the rise of talkocracy — others have called it the dictatorship of the articulate. Talkers standing in the way of builders; offering we ponder, analyze, investigate, research, dissect, agonize endlessly over plans before we lay a single brick.

I for one like Michael Bloomberg’s approach better:

While our competitors are still sucking their thumbs trying to make

the design perfect, we’ve already gone through five rounds of testing.

By the time our rivals are ready to begin development, we are on

version No. 10. It gets back to planning versus acting. We act from

day one; others plan how to plan—for months.

One of my favorite of Uber’s former cultural values was “Let Builders Build.” Some argued it had become “weaponized,” with people invoking it any time they just wanted to do things — as if it was a perverse and extreme side effect, instead of the whole point.

I don’t mean this only as an attack on the timorous — this is about all of us. Fear of change is part of human nature, and we need to fight it deliberately if we want to get anything done.

This endless pondering introduces years and years of unnecessary delays. But worse: it kills the will to build. There is nothing builders hate more than endless meetings with people who can’t even spell “CPU.”

You know you’ve lost when they’ve internalized the conservative voices, which can now stop them without even having to try. It’s when your intern has a neat idea for something he could hack together in a few hours — but then thinks, what’s the point?

What we can do about it

There are a couple of solutions. First, fewer people should be in the room, when there is a room at all. We need to re-create the environment of permissionless innovation that enabled the rise of the modern world, and without which no progress is possible

Second, those who do get a seat at the table need to understand this dynamic, and appreciate the fragility of new ideas before they fight them. Anybody with decision power should think of proposals on an abstract level — instead of wondering what’s wrong with them, they should think in terms of upside and downside, like investors. What’s the worst that can happen if it fails? What’s the best that can happen if it succeeds?

And when we’ve failed at surrounding the table with fewer and wiser voices, we need to be okay ruffling some feathers — we must “move fast and break hearts.”

This is going to be uncomfortable for everybody, and it should be. We should not take for granted the era of unprecedented progress we’ve enjoyed since the Industrial Revolution. History shows that such progress is unnatural, and typically dies quickly. It’s up to us not to let it.

Flo Crivello Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.